What is Embodied Carbon in Buildings?

- Valentine Gomez

- Mar 30, 2022

- 6 min read

Measuring Greenhouse Gases Emitted Before and During Construction.

Excellent article by Margarita Foster, Commercial Real Estate Writer and Editor, Loopnet

Bentall Centre Three in Vancouver, BC measured embodied carbon during a renovation that was finalized in 2020. (CoStar)

Because real estate assets are physical structures requiring initial construction, ongoing maintenance and day-to-day operations, the real estate industry — like it or not — shoulders significant responsibility to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from the construction and operation of buildings around the world.

In fact, Architecture 2030 — a program created by the American Institute of Architects to change the way architecture is practiced in response to climate change — indicated that the building industry generates roughly 40% of annual global carbon dioxide emissions from building construction and operations.

Calculating the “embodied carbon” in buildings is a relatively new area of focus for professionals working toward mitigating the negative environmental effects from the construction and operation of buildings. But, according to one expert, it might not be long before developers are required to meet embodied carbon emission targets to obtain building permits.

Reducing embodied carbon in buildings, however, is no small feat. To understand the concept, LoopNet spoke with Ryan Zizzo, founder and CEO of Mantle Developments, a consulting firm focusing on climate-smart construction, based in Toronto, Canada.

What is Embodied Carbon in Buildings?

Embodied carbon in buildings refers to the greenhouse gases (mostly carbon dioxide) emitted from the manufacturing, transportation, installation, maintenance and disposal of building materials. It is a comprehensive measure of the carbon emitted throughout the “life cycle” of every material — from concrete to carpets — that goes into the base building construction and interior build-out of a building.

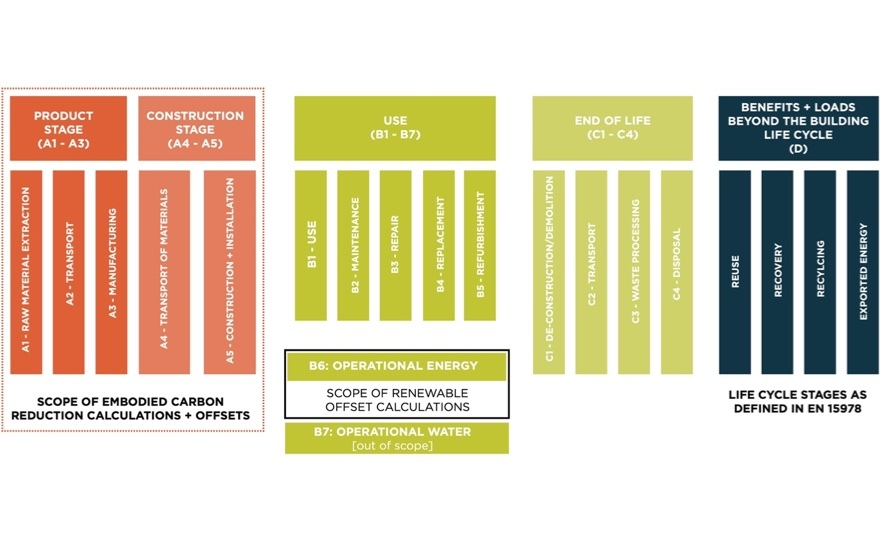

The life cycle process is divided into three segments: upfront, use and end of life. “Life cycle assessment examines the carbon emitted at each stage of the life cycle of a building from harvesting of raw materials all the way to the deconstruction of a structure,” Zizzo said.

(The International Living Future Institute)

The upfront, or product and construction phase, occurs before the building is occupied. It’s a critical phase, as it typically accounts for 80% to 90% of the total carbon footprint of the entire life cycle, Zizzo said. Because of this heavy concentration of carbon emissions generated from all of the construction materials, there's a current movement, Zizzo noted, to focus on the upfront embodied carbon segment and for now, to be less concerned with the use and the end-of-life carbon impacts. This is because those later impacts make up only 10% or 20% of the building’s carbon footprint, require prediction about future processes and what may happen over many decades.

“That's why we're starting to see a shift to focus on the upfront carbon as we get rid of all the uncertainty and guesswork about what's going to happen in 60 years and instead focus on the carbon being emitted today,” Zizzo noted.

Embodied Versus Operational Carbon

A distinction that can help hone the concept is one that exists between embodied and operational carbon.

While calculating embodied carbon involves measuring all carbon emitted during construction, operational carbon measures the carbon produced from heating, cooling — and as the name suggests — the day-to-day operations of a building.

Once a structure is completed, the amount of carbon emanated during construction is set, according to the Carbon Leadership Forum, a nonprofit organization focused on decarbonizing the building industry. This means that there is no way to go back and decrease the amount of carbon released as materials were harvested, processed, transported, etc., during construction.

On the operations side, however, the expectation is that over time, more efficient technology, and increased access to renewable sources of energy will steadily reduce the amount of carbon discharged from annual operations, creating the possibility that less operations-related carbon will be emitted in the future.

How is Embodied Carbon in Buildings Measured?

So how is embodied carbon measured? When the concept is discussed, terms such as carbon, greenhouse gases and carbon dioxide are often used interchangeably, creating confusion for some about what is being measured. These terms are essentially shorthand for all of the greenhouse gases contributing to climate change.

Zizzo explained that when building-related carbon emissions are measured — whether at the construction or operational stages — they take into account all greenhouse gases, but they are expressed in carbon dioxide equivalents so emissions from all greenhouse gases can be standardized.

For example, according to the Royal Institute of Chartered Surveys, one molecule of methane has 25 times the global warming potential of one molecule of carbon dioxide. This means that 1 kg of methane has the same impact on climate change as 25 kg of carbon dioxide and thus 1 kg of methane would count as 25 kg of carbon dioxide equivalent.

Professionals Conducting Embodied Carbon Analysis

To calculate the embodied carbon in buildings, architects and engineers are among the first to become involved with the process. They are tasked with specifying the materials to be used in a building, ranging from concrete and steel to ceiling tiles and flooring. To generate a low embodied carbon number for a building, they need to find suitable, low carbon materials.

Since this concept is in its early stages, not all manufacturers assess and verify the carbon associated with their products, so finding vetted products can be challenging. One source is the International Environmental Products Declaration System. An Environmental Product Declaration is a document that lists the embodied carbon — or global warming potential — of a product or material, enabling one to compare the carbon emitted by various manufacturers of a particular product, such as carpet.

It’s important to note that a product with an EPD is not automatically a product with low environmental impact. The EPD simply provides the embodied carbon data about the product so one can compare it to others. Zizzo suggested that one think of an EPD document as a nutrition label for building materials.

To create EPDs, manufacturers must provide specific data and information required by the ISO, the International Organization for Standardization, a group that, among other things, sets standards for building-related materials and processes relating to embodied carbon. To follow ISO standards, a manufacturer’s EPDs should be reviewed by a third party. Third-party verifiers, approved by the International EPD System, are listed on the EPD website.

Organization’s like Zizzo’s that carry out third-party assessments, review the data and processes outlined in reports written by manufacturers, as guided by ISO standards. These third-party verifiers are required to use an ISO-approved lifecycle analysis tool to conduct their accounting.

These assessments of the carbon emitted throughout the life cycle of materials like steel or carpet, are occurring on an ongoing basis as manufacturers elect to go through the process of gauging their materials for carbon. With these EPD values, products and materials are then eligible to be used in buildings tracking their embodied carbon emissions.

“The ISO sets the rule book … and then it's up to individual consultants to follow those ISO standards,” Zizzo said.

Some confuse the measurement of embodied carbon with comprehensive environmental impact assessment programs such as LEED and the Zero Carbon Building Standard in Canada. However, measuring embodied carbon is not a substitute for comprehensive programs like these. Instead, it is one of many evaluations carried out as part of these broader programs that measure and reduce the impacts of buildings on the natural environment.

Measuring Embodied Carbon is Just Beginning

Concerning impediments to calculating embodied carbon, Zizzo said “it costs money and it’s not a requirement so … you are basically paying money to do something you don't have to do.” But to convince industry leaders, Zizzo noted “you need to show them what value they're going to get out of it,” and that includes illustrating “that you're a leader and forward looking, that you're not doing the bare minimum and that you understand that there is a responsibility in your business to do something that's right for the planet and for the next generation.”

He added that the main challenge today is explaining to business owners why they should spend money now on something that is not required. “We're at the point where it's a voluntary best practice,” Zizzo said.

But one of the points Zizzo makes in support of adopting this practice is that it is “moving from a voluntary activity to a requirement everywhere at different speeds and in different ways.” At the U.S. General Services Administration for example, Zizzo noted that President Biden signed an executive order requiring that newly designed and built federal buildings calculate an embodied carbon score, and use certain low-carbon materials.

And in California, there’s a program called Buy Clean California, “where certain state government purchases require low carbon materials,” noted Zizzo. The program started in 2017 for products and materials procured for infrastructure projects.

He added that in other places like the San Francisco Bay Area, the use of low-carbon concrete is being required and in New York, officials are also starting to look at low-carbon concrete requirements.

There are also policies across Europe. In London, the building code is undergoing revisions to include embodied carbon requirements. Zizzo added that “the federal government in Canada has similar requirements now,” summing up that measuring embodied carbon is the future.

“It's different in every jurisdiction. In some areas the focus is on individual materials, and in others it is on the entire building. In some areas you have to report your embodied carbon, but you don't necessarily have to reduce it, yet. Everyone's doing things a little bit differently,” Zizzo said. But the trend is clear. Embodied carbon management is part of the future of construction.

Comments